all the times i dreamt of dying

initiation rituals of the sad girls club: the art of suffering pt ii

Dearest Reader,

hi! this essay is a continuation of last week's, an introspective on how the romanticization of pain is embedded in culture & society. continuing on that subject, this essay explore the ramifications on a more personal level and how it manifests in media.

please be advised that this post will mention: suicidal ideation, self-harm, violence, and abuse. i will be speaking on school shooters, horror films, cults, and my own experiences with depression. this newsletter is about haunted girlhood, and occasionally will cover topics that some may find heavy. the details of these topics won't be excessively graphic, but if they are uncomfortable to you in any way, i respectfully encourage you to exercise discretion in reading.

i like using memes for levity but as a disclaimer, my intention in writing about all this is NOT to trivialize or glorify harm, but to make sense both of my own life and that of others, as well as how these issues are represented in art.

as always thank you for reading, and if anything in this essay moves you to comment, i would love to hear from you.

cinncerely,

Lana unhappy endings for unhappy girls

I was in middle school when I first began to have suicidal ideations. As with most bullied children, this was a constant rumination of mine. In private, I would research different methods for carrying it out, none of which were really accessible to me, which was frustrating. I didn’t have access to guns or pills to overdose on, and I wasn’t so sure about hanging myself, either.

I knew I needed something foolproof. In my research, I had come to understand the importance of getting it right the first time—if you failed, you could be stuck with an even worse fate: as a prisoner in your body, unable to move or speak, still unhappy but now with even less agency to end it all. But all the ways of blowing out the candle were so agonizing. Jumping off a bridge would be very terrifying. Drowning, I learned, is the most painful way of all. Poison wouldn’t be quick and would be grueling enough to make you change your mind. Cutting seemed too intense, plus bleeding out would take forever. Asphyxiation, no better. And I was already in so much pain, I thought. I wanted my exit to be peaceful. I wanted my last moments to be a prelude to the solace I was seeking, not a nightmare-ish free fall into more of the very misery that had inspired my demise.

Twelve year old me settled, eventually, on starving. It was the only method that didn’t require money, travel or props. So for a week straight, I refused meals. I thought it would be harder at first, but I found that eventually the smell of food itself began to nauseate me, and skipping food was quite easy. I felt proud of my resolve. But this plan didn’t last long. When adults became suspicious, I confided in a school guidance counselor about what I was doing and he explained to me that actually it would take me weeks, months even, to starve all the way to death. And it wouldn’t be painless either, he clarified. Defeated, I gave up, and resigned to living. I didn’t immediately become happier or more adjusted (and frankly my eating habits remained disordered to this day) but I lived. And that was that.

I suppose my philosophy of, I’ve already suffered enough is what kept me from sinking into a more catastrophic level of despair. I felt so much sadness, and I was trying to feel less of it. I daydreamed about running away, or about something terrible happening to me, and tried to imagine who would care. I imagined what a wake up call it would be for everyone who had hurt me to hear that I was dead:

I imagined a room full of people realizing they loved me, that I’d had value in their lives, and the guilt eating away at them because it was simply too late. I was sad, but even in these reveries, I was aware that love and kindness were the things that would soothe me. Unsure of how to access it, I comforted myself with the escapism of books and stories instead.

who hurt you?

Another day, another school shooting. God Bless America, I guess.

The culprit this time was a seventeen year old from Tennessee, and in some headlines you’ll see him described as a “Black Neo-Nazi white supremacist.” I made the mistake of reading the shooter’s “manifesto.” It’s full of crude memes and 47 pages straight of slurs, apathy, and murderous intent, but from what I understand, a good percentage of its contents are actually cobbled together excerpts from the manifestos of other shooters, not original thoughts. Reading the document in full was a mistake anyway, because it left me with a bleak and sour feeling in my spirit that lingered for days, and even now I am still thinking about it. My assessment, having done so, is that his depression, trauma and self-hate were clearly and unfortunately radicalized into rage.

His gripes were not uncommon—feeling out of place and ashamed of your blackness is so standard it’s practically a rite of passage—but somehow he’d gotten absorbed into a cult community obsessed with extreme violence and disregard for life—his own, obviously, but also those of others. He wrote repeatedly of his desire to harm as many people as possible at his school. In actuality, he shot and killed one person (and injured a few) before turning his weapon on himself. He also attempted to livestream the whole thing (another thing the cults actively encourage) but mostly failed at that.

My curiosity about his indoctrination led me down a bit of an internet rabbit hole, and I came to learn there are many such communities preying on minors in this way. Basically, online cults. ‘Members’ are exposed to very graphic content until they become desensitized to violence. They are coerced to hurt themselves, others, or animals for the entertainment of fellow members. Their self esteem is corroded, they are blackmailed and extorted, and eventually members break off to repeat the cycle with their own personal recruits. It all sounds very conspiracy theory, I know, but not entirely implausible considering the world we live in.

Reading about it, I felt so relieved that I had never stumbled upon such a world during my own adolescence. As a vulnerable and impressionable girl online with few boundaries, I had been prey to grooming and toxic individuals in isolated cases. I had recognized that something was wrong although I participated for far longer than a “normal” person would have, because there was still something that drew me in due to my own trauma, but nothing I’d been exposed to had ever been so evil. However, I could have just as easily been susceptible to similar perpetrators.

digital havens for haters

There’s nothing to romanticize in that story, and only so much sympathy you can extend to someone willing to commit such a senseless, vile act, even if we are to believe they are in some ways a victim. But what rouses my curiosity is the twisted way this particular instance of “depressed teen” devolved into such a tragedy in the first place. I wonder a lot about how pain is processed and what behaviors it induces, and I can’t help but wonder about the ways in which these things are gendered.

There are those who decide to make their misery everyone else’s problem, externalizing it as violence towards others—boys are very susceptible to this behavior, most likely due to the way they are socialized to vent anger, one of the few emotions they are unapologetically allowed to access. As proud edgelords, they join group chats where they are goaded into dehumanizing the people around them and joking about homicide, suicide and worse until they build up the audacity to finally the jokes to truth.

The same guidance counselor who talked me out of starving to death also explained to me once that “sadness is just anger turned inwards.” Under this logic, it makes sense then that individuals who internalize trauma might feel compelled to direct further violence against themselves, engaging in various forms of self-harm over the course of their lives:

Sad girls proliferate this behavior through the creation of online communities where they bond over Sylvia Plath quotes and black and white photos of dead-eyed skinny girls rebelliously accessorizing cigarettes. The adult millennials who pine nostalgically for Tumblr’s golden era from their teenage days may recall vividly the romanticization and beautification of depression that circulated in so many photos and made waves across the platform at the time. Sad girls would talk about hurting themselves while taking turns consoling each other, though that sympathy never quite extended to themselves. Their self-hatred overflowed until eventually they found themselves in proximity of malicious actors happy to join in and hate them, too.

radical sad girl theory as a weapon

Pain demands release. Sometimes the release is a hole in the wall, a roaring fist. Other times, it can be tamed into something pretty and presentable: Sometimes “pretty” is a mask for pain.

Take for example artist Audrey Wollen, who in 2014 debuted “Sad Girl Theory,” a series of digital portraits asserting sadness as ‘a tool of women’s empowerment.’ Wollen elaborated that sadness is necessary and has always belonged to girls, operating as the backdrop of our very survival in a world often hostile to our presence. Her work rejected modern feminism’s insinuation that women ought to display happiness constantly despite the reality that pain is often a pillar of womanhood:

Girls’ sadness is not passive, self-involved or shallow; it is a gesture of liberation, it is articulate and informed, it is a way of reclaiming agency over our bodies, identities, and lives. Instead of trying to paint a gloss of positivity over girlhood, instead of forcing optimism and self-love down our throats, sticking a Band-Aid on this gaping wound, I think feminism should acknowledge that being a girl in this world is really hard, one of the hardest things there is, and that our sadness is actually a very appropriate and informed reaction. — Audrey Wollen, Nylon

Wollen’s attempt to explore the role that sadness plays in our lives took shape in the form of languid, dead-eyed Instagram selfies, which garnered thousands of likes. The pain Wollen’s imagery claimed to represent or champion always felt self-conscious and palatable, a little too practiced and polished.

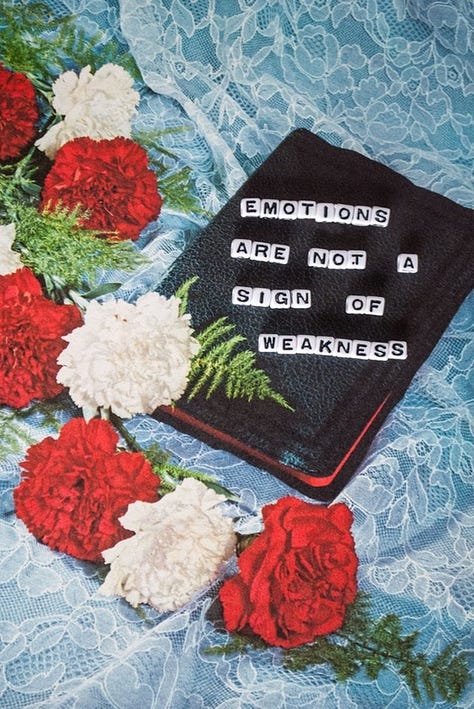

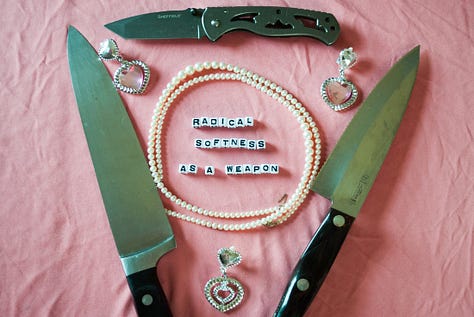

Less than a year later, another artist, Lora Mathis, produced her 2015 photo series, “Radical Softness as a Weapon.” This also made the rounds online. Rather than featuring alleged real-life sad girls, Mathis presented pictures of letter beads spelling out platitudes like “Emotions are not a Sign of Weakness” alongside flowers and knives. Though this juxtaposition of femininity and violence was intended as empowering, it failed to consider the ways in which violence and aggression are already associated with women of color, skewing or obscuring their perception as vulnerable or delicate in the public eye.1

The conflation of softness with violence misguidedly romanticizes what is so often weaponized against self-proclaimed Sad Girls, and typically is, in fact, the root of said sadness. Our predisposition to heartache and trauma need not be a battle cry or a brandished sword, but a condition worthy of respect simply for being a valid response to the many wary conditions of the world.

horror is for the girls

One of the reasons I gravitated towards horror in my early years was that I grew distrustful of happy endings. As I matured and grew older, I learned how to carry myself in a way that encouraged people to think fondly of me and associate me with softness and loveliness in the ways I had always secretly desired. Thankfully middle school was not the entirety of my world: I did not live out the rest of my days being bullied and feeling alone—eventually I changed schools, I made friends, I figured out my personal style, I took refuge in the internet. Things did, in fact, get better.

But there was still a certain comfort I found in sadness, so those were the fictional stories I sought out. I like narratives where circumstances remained bleak, where the victories were unclear. I like the empty feeling and discomfort I am left with afterwards. I remain uninterested in gore and unsophisticated violence, but very emotionally invested in depictions of failure and secrets and doom and death and the eeriness of silence. The little waves of pain.

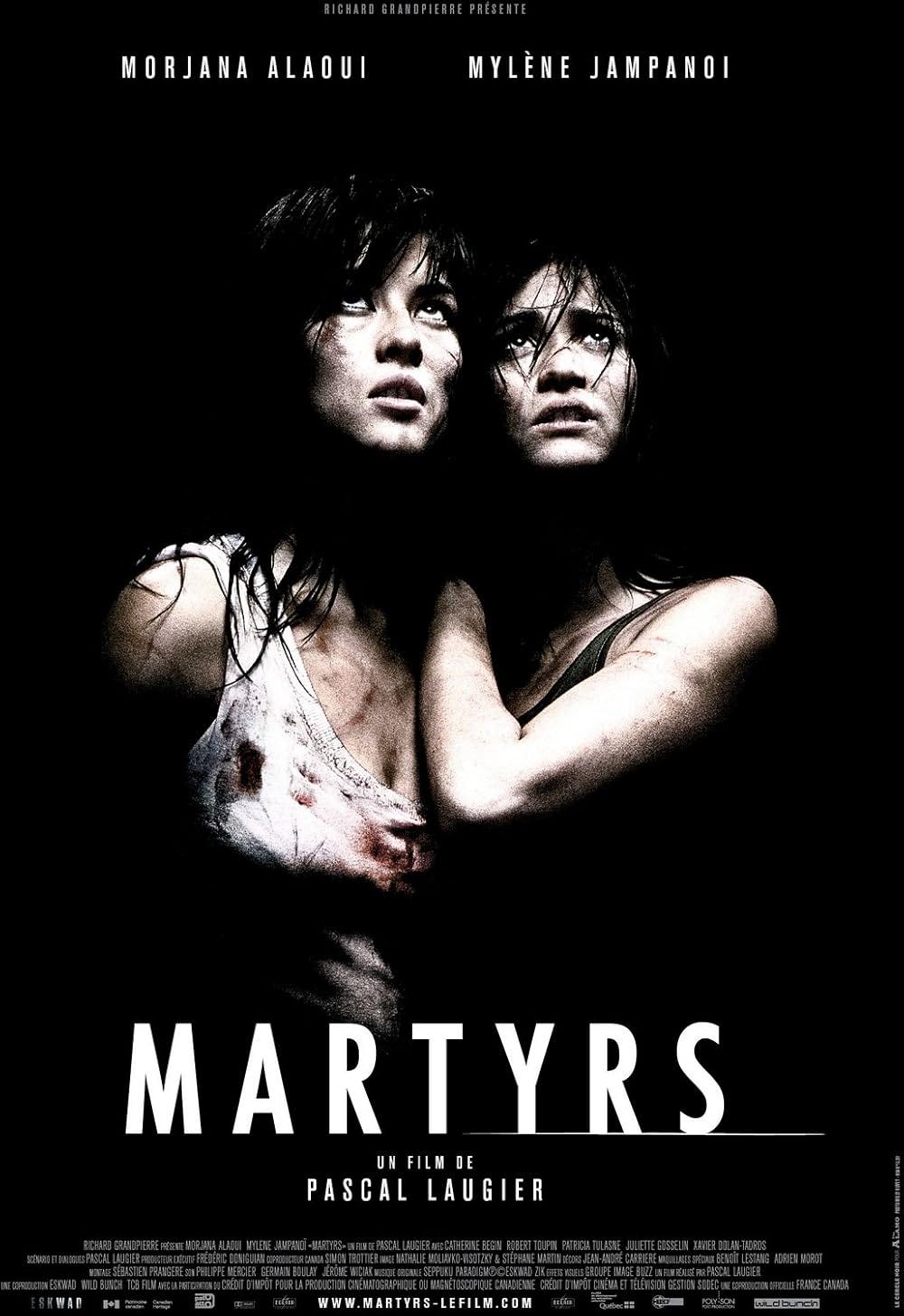

Quick Note: Below, I discuss Martyrs (2008) and Saint Maud (2019). Spoilers ahead if you haven't seen these films!It was many years ago the first time I watched the French film Martyrs (2008). (I had literally googled “most disturbing films of all time” and it was near the top of the list.) In Martyrs, a cult kidnaps and subjects multiple women to ritualistic torture in hopes of producing a “Martyr” able to transcend the pain in order to discover the secrets of the afterlife. The main character, Anna, is a woman of deep empathy attempting to help her friend, a survivor of the cult who escaped as a child and now seeks revenge. Unfortunately, Anna finds herself in the wrong place at the wrong time, accidentally becoming the latest woman subjected to this ritualistic torture—which culminates in her being skinned alive. Ultimately, she is able to become the first ‘successful’ victim of this secret society: the long-awaited Martyr.

Anna’s pain indeed grants her insight into the secrets of the spiritual unknown. We are not told exactly what it is she discovers, but her expression in the final scenes is one of awe.

In the British film Saint Maud (2019), a young nurse, Maud, becomes devoutly religious after failing to save the life of a former patient, as a way of reconciling with this guilt. She is assigned to care for Amanda, a terminally ill older woman at her home and comes to believe it is her calling to help save this woman’s soul before she passes. Maud is hostile towards her patient’s lesbian lover, believing her visits to be a hindrance to Amanda’s salvation, and for this reason is later terminated from her position. Feeling lost in her faith, Maud looks for comfort first by hooking up with a stranger—a callback to her pre-religion days—before ultimately engaging in “mortification of the flesh” (physical self-harm, but Church approved) as a form of penance.

We are given glimpses of a woman with secrets, deep guilt, destructive impulses, overwhelming loneliness. It is fascinating to see the ways she punishes herself out of piety and to witness how her faith manifests as delusion. Throughout the film, Maud repeats to herself the mantra, “Don’t waste your pain.” She is desperately trying to string together meaning out of pain itself, and looking to religion to imbue her with a greater purpose.

In the final scene, Maud sets herself on fire as penance for an act of violence she mistakenly committed in a psychosis-fueled panic. She imagines herself transcending the earthly plane, finally gaining her wings, when the reality is much bleaker.

is god a woman?

In both films, women are conditioned to see their suffering as a means to an end—something that can be transcended, something from which meaning and purpose can derive. Though religious undertones are present in both stories—the terminology of saints and martyrs have strong theological ties—the actual events that take place are clearly removed from anything to do with “God.” But it is from religion that the notion of suffering as virtuous stems, and in both cases, it is women who are compelled to utilize their bodies as vehicles for salvation through their willingness to ‘mortify the flesh.’

no trophy in catastrophe

I do not think pain is meant to be a renewable energy nor do I believe suffering is necessary for growth. As far as I’m concerned, there is no wisdom in any of it, only incoherence and confusion and grief and noise and grasping. There is no path, no solace. There is no quiet in the dark or beauty in the sorrow. I think what joy we sustain, whatever art we manage to create, what we are able to ascertain in these low moments, comes in spite of, not because of suffering.

When I think back to instances of my own heartbreak and anguish, there is no lesson I can impart from any of it, even in hindsight. There is none of it that I would relive. Everything I achieved by way of pain I could have just as easily attained without it.

In real life, trauma is ugly, and I like when it stays ugly on screen. Happy endings trick you into thinking that maybe it wasn’t so bad. Pretty photo ops make you think it looks worse than it is. Pain should not be paraded as an aesthetic just as it should not incentivize bodily harm. Ideally, it is to be alleviated and left behind. And I think that’s what draws me to horror—the honesty in depicting despair for what it truly is: a dead end, rather than a portal or a bridge.

Mathis makes this connection herself on her website, linked above.