How to Live in Hell

How long is forever?

HORROR: A MIRROR OF FEAR

Deep down, what are people truly afraid of? Monsters? Loneliness? Failure? Betrayal?

The horror genre is a popular vehicle for calling attention to persistent individual and societal fears by exploring ethical/political ills, reinforcing or challenging social norms, and reflecting on the dark side of human nature. For example, home invasion and slasher films represent the middle class, suburban paranoia that nowhere is “truly safe.” They peaked in popularity at a time when people legitimately feared their kids could be kidnapped from under their nose or that a serial killer might break into their homes while they slept. Similarly, technological and sci-fi horror consider the blind spots and drawbacks of “human innovation,” whether it’s through accidentally creating a deadly contagion (the origin of countless zombie pandemics) or inciting the imminent robot rebellion (now rebranding as an AI takeover). Psychological horror films prey on the idea that we may not always be able to trust our own judgment—or worse: someone else’s perception of reality can be weaponized against us if we are miscast as an unreliable narrator of our own lives.

As a whole, horror offers a glimpse of the fears that plague us on the macro and micro level.

Personally, I have a fear of imprisonment. It doesn’t feel too far fetched because human trafficking victims literally exist and the equally scary prospect of a spouse who becomes abusive and restricting after marriage or children is not unheard of, either.

Often I think about the real life story of Elizabeth Fritzl, an Austrian woman whose father imprisoned her for twenty-four years in a secret bunker underneath their house. In that time, Elizabeth was raped repeatedly and gave birth to seven of her father’s children. Of the six that lived (one child died shortly after birth), three remained in the basement with her, and the other three lived upstairs and were raised by her parents.1 Elizabeth and her children were only freed after one of the kids became ill enough to require hospitalization. After two and a half decades of torture, Elizabeth was finally able to alert medical staff and authorities to her situation, and escape. (And of course, her father was an old man by then, and admitted to everything).

Twenty four years is a long time. But really, no length of imprisonment is ever quick. I think too, of Junko Furuta, the Japanese teenager abducted and tortured for forty days. On paper, being in captivity for a little over a month almost sounds preferable to two and a half decades until you learn the extent of what Junko endured in those forty days.

Time is always distorted in the presence of evil, where a minute is easily an eternity within itself. I would not switch places with either victim.

DARK ALT REALITIES

Currently, I live a life where I (mostly) get to decide how my time is spent: I wake up. I go to work (sometimes in person, most days from home). If I’m hungry, I choose what to eat and when. In my free time, I can consume entertainment, partake in hobbies, make plans to go out or travel with friends—and I enjoy the freedom to make these decisions every day. What makes imprisonment such a nightmare to me is less about a loss of the option to order Starbucks or shop at the mall and more about being subjected to a reality where my life is suddenly—and indefinitely—a living Hell.

I think about this whenever I watch a zombie film. Stories of abduction and torture are about micro-Hells. A zombie apocalypse, in comparison, is a hypothetical macro-Hell, one into which everyone would be indiscriminately subsumed. Think about it: in every zombie show or movie, the world devolves into chaos faster than anyone can process. Even in those films where we do not explicitly witness the moment it all changes for the worst, we are intrinsically familiar enough with the qualities of a functioning society to grasp all that has been lost.

We watch as protagonists get plunged into a world where their comfort and safety is a thing of the past, replaced by a nonstop onslaught of unpredictable fight-or-flight predicaments. All trace of ordinary life is washed away as a new and formidable nightmare is ushered in to replace the comforts and routines—the former ‘shackles’—of our old world. The line between that “before” and “after” is always so stark, so unmistakable, and so impossible to uncross. That, to me, is the true terror, making the zombie film one of my favorite genres! Like other dramatizations of imprisonment and survival, the zombie genre captures a reality so profoundly void of hope yet fueled entirely by the pursuit of it and the illusion of its presence.

In the early scenes of an apocalyptic drama, when the panic is rampant and disbelief still has reign, we follow some protagonist as they flee to “safety,” expecting to quietly wait out the sweeping devastation and despair until some Hero can swoop in to save them: the military, a brave lover, a gang of vigilantes. Eventually, they realize, as do we, that no one is coming. There’s no cure on the way; society won’t be rebuilding itself anytime soon.

Once the world has fully descended into the domain of the depraved and the deprived, violence and power become the dominant currency of the land. Our main characters quickly realize the need for weapons, wit and at least one trustworthy companion if they hope to survive. In zombie shows, survival hinges on resourcefulness and bravery and strength as much as it relies on community and kindness. Because eventually the food runs out. Or your safety gets compromised if one day a knock comes at the door. And in those moments, protagonists must be ready to test the boundaries of their own morality lest they be subjected to the limits of someone else’s mercy. A Hell within a Hell.

What’s the point?

When I consume these stories, admittedly I struggle to understand the motivation to live in a world where your neighbors pose as much of a threat to you as the snarling undead beast that hungers to eat you alive. What is the point of an existence where normalcy is a thing of the past? When the world will keep turning, and will turn away from you too, as it turns into something beyond recognition, a horror of unfathomable proportions? In the wake of that great catastrophe with no reason and no resolution, I would not be among the survivors clinging desperately to the scraps of my humanity. Many people love to daydream about how well they would fight and scavenge in such a scenario, but not I. I think death is often the only peace to be found in such cases.

When the apocalypse comes to collect, I do not intend to fight it. I do not intend to don a suit of armor, I do not intend to take up new skills and struggle to somehow make Hell bearable enough to live through. What for? As I watch these films, I always wonder if that’s what the early days of mankind were like: an endless wreckage of blood and lawlessness. What a poetically hopeless situation. For even if you could eradicate every undead monster in that timeline, what new world would you build in its place? With what infrastructure? Rather than wait around to find out, I hope instead, to fade away quietly, without much suffering if I’m lucky, and to quickly be free of the horrors that are bound to compound with the unending passages of time in a reality marred by carnage.

But…what if the choice to leave—to die—simply wasn’t an option?

In that circumstance, to live would then be a special kind of torture, no? I’ve noticed that in stories depicting the various sorts of micro-Hells that are possible, such a fate is revealed to weigh heavier with devastation than the simplicity of death’s finality.

HOPE IS A NORTH STAR

Hope is the driving force of human survival, for a life without Hope is seldom lived willingly. Were it not for the belief in the possibility of a timeline not so acutely defined by suffering, there would be nothing to coax humanity away from suicide in the face of adversity. Hope is often clung to by force, forged from absurdity, shapeshifting as the situation demands. To Hope is to Imagine. To Hope is to Live.

Thus, Hope is central to the survivalist genre! And the story of surviving a zombie takeover is not too different than the story of surviving a natural disaster or slavery or a pandemic or an abuser. Whether it is Hope for a cure, or a savior, justice, or a restoration of “order” matters little, so long as the idea of something beyond oneself remains to attach to and strive for.

Recently, I’ve read a few books and watched some movies that explore the idea of making Meaning out of very little while enduring different kinds of Hell. These narratives, discussed in further detail below, describe being stuck on a spaceship, in an attic, in the wrong body, in a cage—and then later a strange, abandoned landscape—and lastly, in a supernatural library. Again and again in these stories, I notice that the survival strategies of the characters are shaped by the contentious relationship between Time, Hope and Meaning (or the lack thereof) within the context of their experiences. Each story illuminates something interesting about what drives the will to live as characters adapt to the existential angst at the heart of their plight.

It seems, according to these texts, that Hope is in Greatest Abundance when Time is Short, and where there is Hope there is Meaning. But Hope lessens as Time lengthens, and Meaning typically dwindles with it if there is no activity that can occupy the Time instead. In other words, the longer a character remains in a Doomed Situation, and the longer this Doom seems inevitable and unchanging, the less Hopeful they will be. Yet Meaning may still be made even in these bleakest moments, because when Hope is in short supply, many people will settle for Purpose.

Flowers in the Attic

In the novel Flowers in the Attic by V.C. Andrews, after their mother is widowed by a tragic accident and left without any financial means to support her family on her own, four children arrive in the middle of the night at their grandparents’ mansion and are quietly stowed away in the attic. “You will only have to hide here for a day,” their mother assures them. Her dying father, she explains, has disinherited her and removed her from the will because he didn’t approve of her marriage. And he doesn’t know she has children. But, good news! All she needs to do is get back on his good side, get herself reinstated in his will, and then as soon as he dies, she’ll collect her inheritance and the five of them can live happily ever after all the way to the bank.

After their first night in that dreary house, the children remain optimistic. They love their mother, and she’s never given them reason to doubt her before, so why start now? So when she reports back to her disgruntled teens and toddlers the next day that she needs more time, that things are trickier than she initially expected, of course they are understanding. Though they haven’t met their ill and dying grandfather, they have already grown acquainted with their Grandmother, who certainly seems evil, and so they imagine he’s not much different.

Of course these things take time. That seems reasonable. Okay. Sure, the room they are locked in has already begun to feel claustrophobic, but even as the older children— twelve year old Cathy and fourteen year old Chris—begin to feel doubtful, they try their best to concentrate on making things as comfortable for their five-year-old twin siblings as they can.

Days go by. Weeks go by, then months. By Day One Hundred, they are no longer as optimistic as they were on Day One. Slowly, they become convinced that their Mother is not being entirely honest with them. They question her at every turn. They argue with her. They poke holes in her excuses. As their trust in their mother recedes, Chris and Cathy become more and more committed to their roles as Replacement Parents to the twins so desperately in need of love and guardians. Whatever Hope they lose, the eldest children make up by creating meaning for themselves.

Has their Mother truly forsaken them? Will they really never again see the sunlight or enroll in school? Will they die here, in the attic? The answer cannot be yes, for the pale hope of someday again being free is the only thing keeping them alive, keeping them faithful to their mother, to each other.

Locked away up there, Time has slowed down. Having so little to do, the children fill their days with dreams of alternative futures: they remember what the World used to be for them, the Possibility and Color it once filled with before all their days were confined only to the sunless walls of that attic.

Aniara

It is a similar story in the film, Aniara. When Planet Earth becomes uninhabitable, hundreds of people board a spaceship, Aniara, en route to another, more hospitable planet: Mars. There, their families and their new futures await. The voyage typically only takes three weeks and the ship is like a cruise vessel, full of luxurious amenities, entertainment, and plenty of food.

Three weeks in Paradise? No problem! What about two years, though?

A collision with floating space debris knocks the ship off course and causes the flight crew to offload their fuel supply to avoid further damage. Without a way to independently get back on track, the Captain explains via intercom, their new plan is to wait to pass another celestial body and use its gravitational pull to steer the ship back onto course. It’ll “only” take two years. The passengers groan, but these things happen, don’t they? Space travel is probably prone to menial complications like these all the time. And the Captain knows what he’s doing, right? And besides, at least there are heated pools and comfortable beds and people to talk to or hang out with and tons of delicious food to eat and unlimited entertainment to enjoy. All of this is certainly better than Earth was when they left it behind, and two years in space is a small price to pay for a cozy lifetime on Mars…

So no one complains too much, not at first. As in Flowers in the Attic, Hope is manufactured and artificially stoked through faith in an authority figure resistant to questioning or doubt. If the Captain says he needs more time, who are you to tell him he’s wrong, especially without any counter-knowledge of what it takes to steer a ship to another planet? So, Hope persists. For the next two years, Time moves at a slow but agreeable pace and Hope persists as Mars grows closer in reach each day.

But then comes year three. Followed by year four. Unsurprisingly, by year five the waning Hope of ever reaching Mars causes suicide in droves. The triple combo of mass death, captivity and creeping doubt begins to take a toll on the leftover living (and increasingly anxious) passengers. Looking around, they ask themselves, Now what? For those not quite ready to commit to Death and desperate to cling to what little optimism they still have, cults fulfill their need.

The human desire for comfort prompts people to seek out objects or charismatic individuals to soothe their fears and anxieties. To resolve the lack of purpose felt by those trapped on Aniara, a fertility cult emerges and hosts a group orgy, resulting in multiple pregnancies. Newborns on a lost spaceship hurling fast towards Nowhere hardly sounds like a bright idea, but it does succeed in providing travelers something outside of themselves to focus on. When the Captain instructs his crew to start teaching the children on board about astrophysics and space travel, in hopes their fertile young minds will be instrumental to finding a solution, it reinforces the notion that procreation is indeed an effective method of restoring Hope where previously none existed.

A Word on Apocalypse Kids

Stories about surviving the world’s end so often toy with the subject of children. If life bears no meaning and the world is doomed, to impregnate someone or to willingly give birth seems mind-bogglingly irresponsible, almost cruel even. As much as I understand the scarcity of contraception in these situations, I can’t help but roll my eyes whenever a pregnant woman waddles onto screen during some apocalypse show, and I sigh loudly when side characters put their own lives at risk to save hers or her baby’s.

The biological imperative in these contexts always strikes me not as a noble gesture but instead as an ill-conceived and unfortunate bid for Meaning. The child in those situations is, at once: a physical manifestation of the passage of Time (which naturally starts to feel abstract and unmoving during periods of extreme monotony), a call to action (and a symbol of that effort so long as they remain alive), as well as the ultimate embodiment of Hope itself, for children teem with Possibility where they bring their youthful curiosity and defiance. Death may not be inescapable, but through offspring it can be spiritually prolonged.

I Who Have Never Known Men

In the novel I Who Have Never Known Men by Jacqueline Harpman, forty women are kept locked in a cage, watched over by three guards at a time. The women have been locked up for over ten years, maybe longer, and they only have some estimate of the length of their capture because of the little girl among them, whose inclusion certainly must have been an accident.

They do not know their captors’ motivations. The women only know that they are forbidden to touch one another, forbidden to commit suicide, forbidden to leave. They have lived in captivity, drugged on the regular they suspect, for so long they can recall almost nothing anymore about who they used to be. In fact, the women had long given up all hope of ever escaping or receiving answers until one day, miraculously, a strange accident—a stroke of luck—granted their freedom.

I Who Have Never Known Men is written from the first-person perspective of that “child” who was never given a name or referred to by any other title even after she grew adult. As she grows and ages, The Child serves as a living marker of Time, a glaring reminder of how much has passed since they all were snatched from their old lives. But unlike her fellow former inmates, The Child is not full of longing for the “Old Days.” Nor is she as defeated by the lack of explanation for their circumstances. Having been raised solely in captivity, The Child has no memories of a Before. She cannot conceive of a livelihood beyond the one she lived and lives in, no matter how many questions she asks, though she asks many. She cannot even be moved by the selfish urge to fulfill herself through an infant, because in this world men, too, are a relic of the past.

Throughout the book, The Child remarks on how different she feels from everyone because of her unique upbringing. When she lived in the cage, she only imagined what it would be like to not live in the cage. But then that dream came true. Post-imprisonment, with everyone’s basic physical needs met and no looming threats endangering their newfound freedom or safety, there isn’t much else to Hope for, besides information. Even then, there were limits to what The Child could learn and know because there were limits to what the other women could teach.

The grief of longing for an experience not your own is distinct from nostalgia shaped by organic and personal memories; the intensity is weaker.2 Lack of Memory stunts Imagination, which in turn lessens the inclination to Hope, removes the urgency to search for Meaning, and dulls the pain of Time’s unending passage. This is the bliss of ignorance in action. With nothing at all, better or worse, to compare it to, Hell inevitably becomes synonymous with Home, and that was the critical difference in perspective between The Child and the women she lived in community with. This was likely also the case for the generation born on the Aniara.

HIERARCHY OF NEEDS

In the works I’ve presented so far and the ones I will go on to mention, the authors address early on the matter of physiological needs being satisfied before pivoting to the more existential problems their characters face. At the onset of their imprisonment, the fictional people we follow are provided food, shelter, a place to sleep and even companionship, since solitary confinement would undermine and void the meeting of all other physical requirements.3 After all, when people are left to scramble for resources to ensure they live to see another day or experiencing their sanity self-destructing in real time, stories about survival take on a different focus because there is little room to philosophize about the point of living.

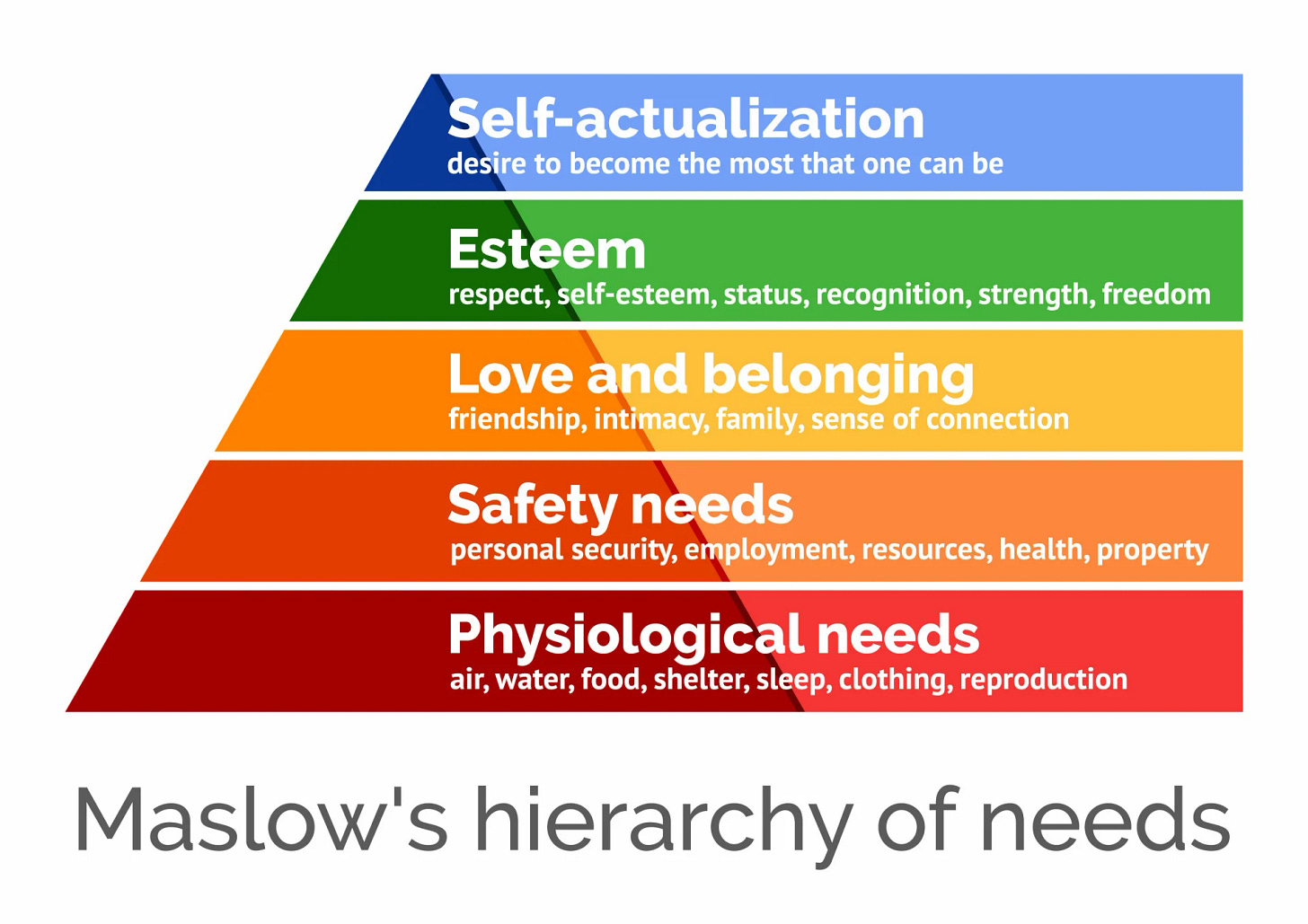

This corresponds with the hierarchy of needs proposed by psychologist Abraham Maslow, where physical needs lie at the base level. Published in 1943, Maslow’s theory attempts to explain motivations for human behavior. From bottom to top (and in order from basic to most advanced), the five needs are: physiological, safety, love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualization. According to Maslow, and as most fictional and real-life narratives reinforce, physiological needs4 are non-negotiable and fundamental.

It is also important to understand that these needs, though referred to as a hierarchy, do not follow a rigid cumulative procession. That is to say, a level of need can be partially met before moving on to the next stage. These needs are interrelated and often met in overlapping waves.

In none of these stories do the characters evolve to the stage of achieving esteem or self-actualization. Imprisonment inhibits reaching your full potential, so that’s always off the table. It is also difficult for people to feel good about themselves under such circumstances, so feeling esteemed is tricky. Most stories centered on surviving confinement to an enclosed, isolated space hover around the lower three tiers of needs, specifically the second and third: safety and love/belonging.

Safety in particular is a very contentious and precarious state. Absent a constant threat of physical violence, and with most physiological needs met, some might say these books contain pretty cozy Hells. They could almost be described as “safe” if you overlook the lack of freedom thing. It is easy to be lulled by the illusion of safety, and in some cases, characters fail to progress to having their other needs fulfilled for this reason.

A nice Hell. I laughed at the thought. This wasn’t a bad place. It seemed like a tedious Hell, but there was plenty to eat, good company, and it sounded like after a while we would eventually get out.

— A Short Stay in Hell by Steven L. Peck

I Saw the TV Glow

The film I Saw The TV Glow depicts the experience of being trapped in the wrong body, in a fake world. Owen, the main character, doesn’t realize this is their situation though. Their life isn’t particularly joyful, but they don’t really complain about it. The acceptance of their circumstances as normal and immutable relieves Owen of any desire for change. When their equally unhappy friend, Maddy, suggests running away to go somewhere (anywhere!) better, Owen panics and chooses to stay because they can’t imagine being anywhere else.

One day, years later, Maddy comes back. “Remember that old TV show we used to watch together as kids?” she says to Owen. “That stuff really happened—it happened to us. You need to get out of here.”

Owen is taken aback by the implication they have been living a lie. And now Maddy wants to run away again, but how can Owen leave? They have a dead-end job, a house they live in with a father they don’t love, and no friends—who wouldn’t want to stay? If anything is wrong, it must be Owen, not the world. This is Home, not the show they watched as kids and not the vast world of the Unknown that exists Out There.

For Maddy, the show she and Owen watched is a lost memory, or an invitation to dream. Because of it, Maddy is able to conceive of a life alternative to the one she experienced during her adolescence. She looks at her small town and her toxic parents and her boring high school and she understands that something better is Out There. She understands that her needs are unmet, and that they will remain that way if she stays.

Unfortunately, that isn’t true for Owen. Unlike Maddy, Owen lacks both memory and imagination. Even when they do feel discontent, their denial keeps them complacent till the negative feelings pass. To Owen, a foreign Heaven is worse than a familiar Hell. As long as nothing is wrong, nothing needs to change. Owen never experiences safety, love and belonging, or self-actualization because Owen mistakes having a place to sleep and something to do with the totality of the pyramid.

THE ROLE OF MEMORY IN SUFFERING

You know how the Roadrunner stays suspended in mid-air after he runs off the cliff, and doesn’t start falling until he looks down? I think memory and suffering are a bit like that.

If you “step off the ledge” but realize it quickly, you might be able to grab onto something and scramble back up to the top—your success would signify a return to the status quo. Hope, in that case, is not the tool you reach for first; your reflexes and wit are what you’d need to apply. If you step off, realize your mistake too late and the drop isn’t too steep, you might not be thrilled about falling but you also won’t panic. Maybe after landing you can’t (or won’t) make it back up to the top, but you’ll be ready to move forward and figure it out. But if you fall off the cliff and it’s a really, really long way down, now you’ll probably start hoping: for minimal injuries, for medical assistance, for a map to make your way to safety when it’s over, to live.

A longer drop parallels a longer span of time. The need for Hope is reliant on the passage of Time. If Time stands still, Hope stands still, for Hope is a measurement of the distance between the Bad Times (now) and the Good Times (both the ones back then and those soon to come). Awareness of the Bad Times relies on memory. Anticipation of the Good Times requires both awareness and imagination. For some, it manifests as yearning for the past. For others, it’s enough just to no longer be in the present, even if things never do return to what they once were. Still others ideate new possibilities for themselves entirely. For those who Remember nothing, the distance between their present reality and their desired reality is so minuscule as to be nonexistent. They are exempt from the tension of feeling “stuck” in the wrong time.

After all, if you never even realize you’ve stepped off the ledge, then you never notice you’re falling. This doesn’t mean you’re not falling, nor does it absolve you of the consequences of a hard landing. But it encases you in a bubble that changes your experience of the situation, and it changes the way in which you suffer. For example, individuals with Alzheimer’s or dementia exist in a state of obliviousness that their grieving loved ones do not, but ignorance does not change their fate.

Importantly, denial differs from ignorance but lends itself to a similar kind of stupor before the bleakness of reality fully takes hold, during that time in which a happier future remains a distant dream but the past is not yet far enough away to lament. It’s serene there for a while, before the panic kicks in. Just like when the Roadrunner is still in mid-air.

Without restrictions on their autonomy, for most people the distance between the Good and the Bad Times is not that great, making the gap usually easy to close. Confinement widens that gap. In their endeavor to close it, prisoners reckon with the difficulty of the task ahead. Is change truly possible? If yes, then Hope persists and efforts towards change are made.

Change takes many forms. Obviously, escape is a change, the Ideal change. Death is a change, too. If the distance between Now and The (New) Good Times is too great, Death may be the next best option to some. If Death is not yet more appealing than waiting for or creating Change, but Change remains distant enough to threaten Hope, it may be wise to employ denial. With Denial comes acceptance or complacency, but if Now is the only Time there is, it only follows that your new objective should be to find a way to make it Good, even if lying to yourself is required. If Denial is not possible, then Distraction is equipped; as we’ve seen, this is the utility of becoming a parent or having a task at hand.

In Flowers in the Attic, the children use Denial and Distraction to maintain Hope while enduring the awfulness of their mother’s betrayal. The passengers of Aniara do the same when they realize they may never land on Mars. The women in the strange universe of I Who Have Never Known Men bide their time with Distractions while waiting one by one to Die, since it is not possible to deny what has happened to them, as much as they try to forget. Owen of I Saw The TV Glow is unable or unwilling to acknowledge things are Bad, and therefore is doomed to endure being miserable without ever confronting that Change is both possible and attainable.

A Short Stay in Hell

If the obsolescence of Hope results from the absence of memory, does Time cease having significance if Death can no longer taunt humanity?

A Short Stay in Hell is a novella by Steven L. Peck5 exploring the true incomprehensibility of Time. After dying, Soren Johansson arrives in the Library of Babel, a realm filled with books. Each book is exactly 410 pages. Each page contains exactly forty lines of eighty characters each. The books and the library are modeled after the short story by Jorge Luis Borges, which imagines a library containing every permutation of a 410-page book in this format that could possibly be written—so there is a book of only the letter A on all pages, a book of only the letter B, one of just commas, and so on.

Soren’s assignment—and the assignment of everyone else alongside him sent to this particular Hell (it is not the only Hell available; others exist)—is to find a very specific book: the one containing his life story. This is the literary equivalent of finding a needle in a haystack, but he doesn’t realize it at first—none of them do.

Inhabitants are given sleeping quarters and a kiosk that will serve them any food they ask for. If they die, they wake up again in the morning, all injuries healed. They have perfect memory, full recall of their past lives, and can’t forget anything. The only way to be freed from this existence is to find their book, a task easier said than done. Day after day, he and the others in this Hell pick up books off the shelves and scan their contents one at a time before chucking duds over their shoulders into a deep chasm. Most books are pages of gibberish.

“The thing that has the most meaning to us here, the book with our life story, will be found in ten years. It gives the times and seasons of our stay here. It might mean ten days or ten weeks, but I suspect given the magnitude of our task ten years is not unreasonable.”

“Oh,” I said.

Dolores was not too happy with his interpretation. “Ten years? That’s a long time to stay in a library. I hope it’s days or weeks. My heavens, ten years. Here. We’ll all go batty.”

As stated earlier, Time is a prerequisite for the existence of Hope. But paradoxically, the more Time that goes by, the more Hope whittles away. What happens thusly when a year becomes indistinguishable from a day? When a billion millennia blink by with the indifference of a month? Without even death to aspire to, the inhabitants of the Library of Babel truly have no choice but to commit to their assignment, as abandoning it would mean abandoning freedom, abandoning themselves.

Though a faction of residents do deviate from this original goal—a cult compelling people to commit ritualistic acts of extreme violence as an alternate path to salvation eventually arises6—other individuals, like our main character Soren, continue day after day to Stay on Task. It may take more years than the human mind is capable of even fathoming, but the mythical book that will set him Free exists, and one day he will find it. The act of doing something, he eventually comes to understand, no matter how tedious, confers Meaning. And Meaning is at the heart of Existence.

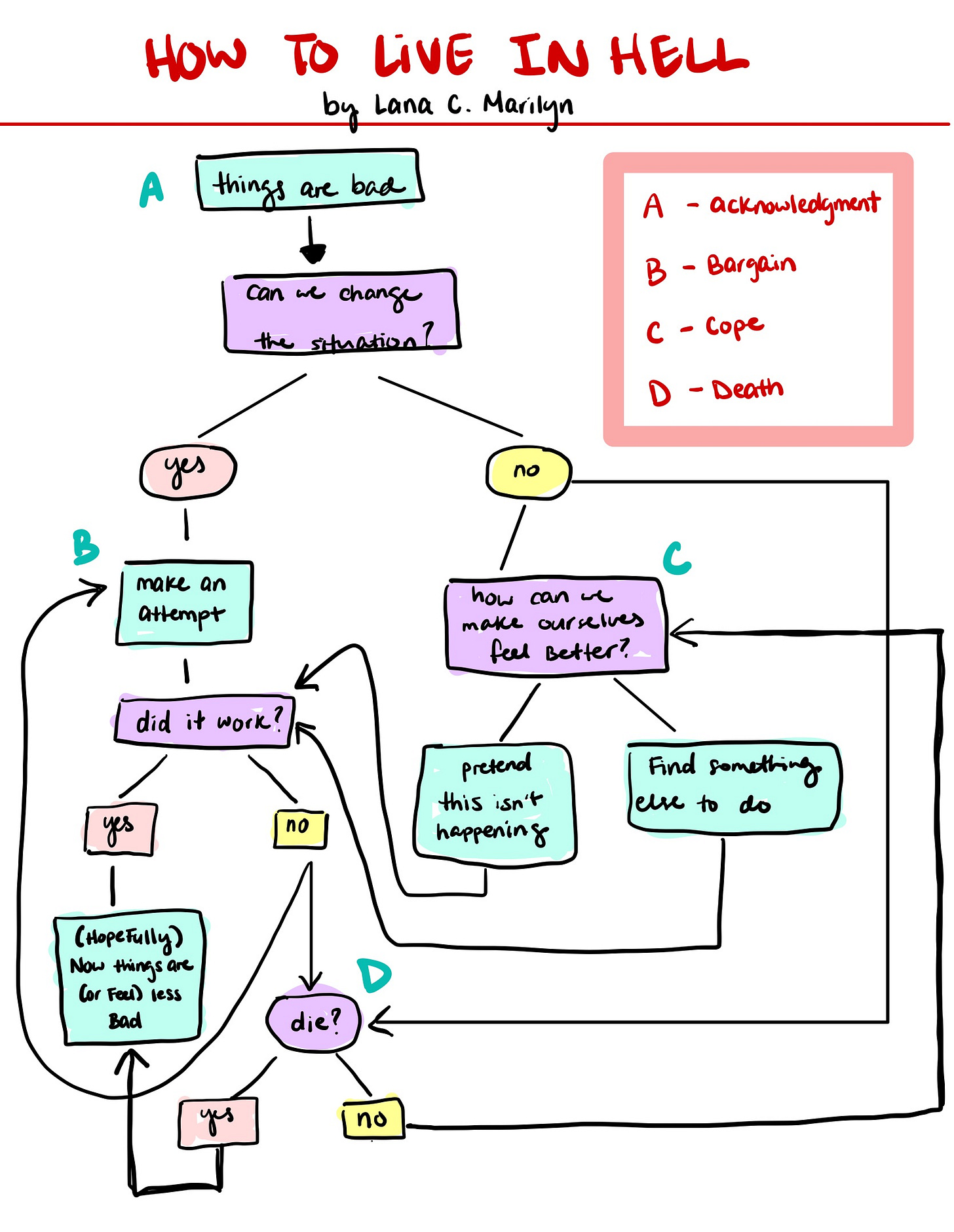

TL;DR HOW TO LIVE IN HELL:

Recognize and acknowledge that you are, in fact, in The Bad Place.

Attempt to escape or materially alter your circumstances.

Repeat step two until it works or you get fed up.

If you do get fed up, consider unaliving yourself.

If step four is too intense, find a way to cope by either distracting yourself or finding something to do. Or, you could give step two another try.

Repeat step five until it works or you get fed up. If the latter happens, see step four.

Elizabeth’s mother believed her daughter to be a runaway repeatedly leaving newborns at their doorstep because she recognized she wasn’t fit to raise them herself. That part of the story always challenges my suspension of disbelief because it’s so absurd, but the mother believed it because her husband said so and produced handwritten letters (that Elizabeth was obviously forced to write) stating such, and these were shown to investigators handling the missing persons case as well.

Think of all those people who’ve lamented “being born in the wrong generation.” Their nostalgia is artificial and manufactured. What would their longing look like if they had no old movies, old clothes, old songs, books or art to reference? Nothing but fragments of stories from old people, and strangers at that. Ones too unwilling to talk about their history because of the pain that remembering drags to the surface. When your life has only been a blank wall and you are untethered from all your history, do you not then exist someplace between Time? In a liminal space stranded between the Old World of the Past and a Future you lack the capacity to even Imagine?

Individuals trapped in isolation are without any means to create purpose for themselves and are therefore more susceptible to suicide since they have no distraction from their own loneliness and despair. You don’t even have to like or get along with the people around you, the mere fact of not being 100% alone is crucial to mental health. Studies indicate it is torturous for a person to be in isolation for longer than 10-15 consecutive days, and signs of trauma are identifiable around this mark.

More specifically, these include: Air, Water, Food, Heat, Clothes, Shelter, and Sleep. Some lists include “sex” but I don’t think anyone has ever died of celibacy (sorry, incels). However, I would argue that companionship is a base physiological need because humans are fundamentally social and prolonged isolation & sensory deprivation cause longterm trauma and psychological damage. Babies have literally been known to die if left untouched for too long!! Severe lack of physical contact can stunt their growth significantly, a phenomenon often referred to as "failure to thrive.”

I found a site where you can read the novella in full for free—enjoy!

This was the scariest part of the book for me, because physical violence and torture in a realm where no one can permanently die seems so much more severe for the victims.