the ones we tell and the ones we keep

a moment of silence for the alternative futures my foremothers might’ve lived under kinder circumstances

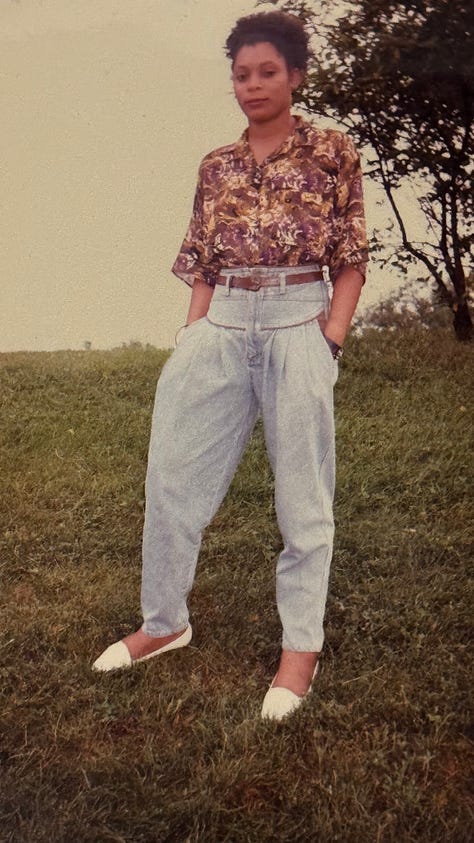

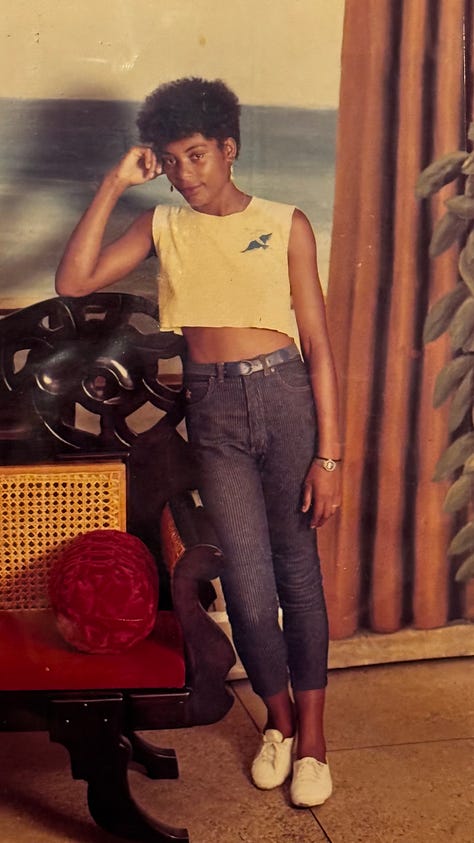

My mother was born in 1966 in the island nation of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, an archipelago located in the Lesser Antilles of the Caribbean. She grew up poor. Her father was a violently abusive alcoholic who couldn’t read, but I’ve been told he was very good at math and a skilled fisherman. His boat, rotting and faint of color, sits parked in a grassy field by the bayside, where for years it has remained untouched by all but sand and wind and rain. A tombstone. When I visited the island for my grandfather’s funeral, my older cousin—a fisherman himself—pointed it out to me, and for a moment I rested my gaze on it quizzically, struggling to imagine him out at sea. I’d met my grandfather only once before he died. He was nothing like the man I’d heard stories about. Rather than strapping and serious with leathery skin, he was shriveled. Confused. Docile, even. A shark without teeth. His dementia was so acute on the day I met him that he couldn’t register who I was, so he never met me back.

My grandmother, who would later come to America when I was three to help my parents raise me and my siblings, cleaned houses for a living in the days of my mother’s youth. Given her quality of life, my mother understood from an early age that education was “her ticket out.” In 1971 (eight years before the country would declare their independence from the British) at age five, she began primary school. It has been explained to me that school was free but not compulsory, so if children decided to skip classes and fool around behind their parents’ backs, or if they dropped out early to work instead, there was no one to interfere. I am told this is why my uncles are illiterate.

“Growing up, most of my siblings...didn't have that opportunity. I don't know what happened to them, why they didn't even get that chance. But it was very important for me, because I remember seeing them and the limitations that they had, and I didn't want that for myself.”

When asked about her experience of school as a child, my mother recalls having a strong dislike for physical education activities like track or field, but that she had enjoyed math and science. She went on to enjoy reading as well, though books were allegedly hard to come by. “We didn't have libraries and things like that,” she tells me. When I do some research, I learn the first library on the main island was opened in 1910, yet they actually weren’t free to the public until a few decades later, in the 1950s. According to the official government site, a library was opened in my mother’s neighborhood, Calliaqua, in 1952, within the local Town Hall. I tell her this but she insists that despite living right across from the town hall, she had no knowledge of the library’s supposed existence. There are now 21 library branches within St. Vincent, most of them only established within the last century. I browsed through the National Public Library located in the island’s capital, Kingstown, while visiting this past July.

My mother’s childhood memories of acquiring books involve asking neighbors for secondhand copies—older children were more than willing to hand off the (now obsolete) books they’d been assigned to read years prior—or borrowing them from her sister, who, while working as a live-in maid for a wealthier family, had plenty of access to leisure reading material, like Nancy Drew.

The years went on. Though she would be forced to drop out from secondary school after my grandmother could no longer afford it, a few months before her 21st birthday my mother finally managed to emigrate to Canada thanks to the kindness of a family friend. Against the odds, she’d made it out. After that, except to attend funerals, she barely ever ventured back home again.

I am told I was a quiet, precocious child. That I liked trying to help. As an adult, I understand I was probably born anxious. I am told that as a baby, I used to wake up in the mornings before my parents, watch them sleep and wait for them to rouse before I started crying. As an adult, I understand that I haven’t changed.

I was born July 31, 1994. Was barely two when my first sister was born; my parents kept cramming new siblings into our two bedroom apartment like they were limited edition collectibles. For a while, it felt like every year a new baby materialized. My earliest memory, in fact, is turning four and my mother calling from the hospital to wish me happy birthday and tell me that my second sister had just been born the day before.

And yet, I recall being a lonely child. Sometimes I managed to persuade (i.e., bully) my sisters into playing with me, but most often I sat alone playing with my toys, an assortment of barbie dolls and random figurines from happy meals. Each had a name. Pretending they were all citizens of a magical town inexplicably named Totem Pole, I acted out and narrated their adventures aloud, like an episodic puppet show. That was the way I crafted stories before obtaining literacy.

I learnt to read using Hooked on Phonics. The details of those memories are fuzzy, but I remember the commercials, and the colorful packaging, the cassettes, and the flash cards and the books. I remember doing these exercises on my own. I remember reading a lot by myself at home, lots of Dr. Seuss. And my father liked to sit me and my sisters down on weekends and teach us for hours about the branches of government and the different parts of the body. Though I found this painstakingly boring, I took an interest in his medical books when I discovered the glossary at the back for all the special words they used for ailments and anatomy. Affixes like “-itis” or “gastro-” became fun clues for guessing the meanings of big complicated grown-up words and suddenly language was a game.

As soon as I had a grasp on reading, I was writing. It was fun. And easy. In elementary school, we’d get weekly spelling lists and instead of writing one sentence per vocabulary word for homework as instructed, I’d challenge myself to create a short story incorporating the full list. I was trying out all sorts of things before age ten: I wrote picture books and comedy skits, tried to start a magazine with classmates (and we did release and circulate a few issues!), and by fourth grade I was writing a chapter book and typing my novel on the computer and creating not only stories with characters who spoke secret magical languages, but glossaries of vocabulary and sample sentences to match.

Everyone strongly supported my creativity. My teachers entered my classmates and I into bookmaking contests and helped us create hardcovers of poetry through partner organizations. They let me read-aloud my writing at story time or for ten minutes at the end of a school day if time permitted. I suppose they imagined I’d be a famous author by now, so maybe it’s a little disappointing I haven’t yet lived up to that expectation. But as a child aspiring to be a writer, I benefited immensely from their sincere encouragement and patience: I wrote and wrote and wrote, absorbing myself into the fantasy worlds of my own creation. As an adult, I question if this was a form of escapism, born from a desire to be someone—anyone—anywhere else.

"Back home" was a phrase I heard often growing up, a quiet reminder that the country we lived in did not belong to my parents or my extended Family—as contentious as notions of “belonging” are for any displaced peoples, there was still an understanding I had, early in childhood, that our presence here was unprecedented. I began to wonder whether it Belonged to me, either. I found myself always longing, dreaming of it: “back home.” This other place. Other home. One I could never fully imagine, though I had touched it once, or so I was told: when I was barely a year old, my mother sent me to the island with my paternal grandmother, who dropped me off with my mother’s family, where I remained for roughly three weeks. There are no pictures of me from this trip. But I am told my uncle paraded me around the streets, excitedly showing off me, his newborn niece. That uncle died in 2002, and I lament never having had the opportunity to meet him. (But I’m grateful that he met me.)

That I had already once been to the country that haunted me only heightened my fervor to return—it became mythical. My childhood concept of place back then was limited to our house and my school and my aunt’s house and department stores and the backseat of the family car. It was a small world. And knowing there was another world I was tied to, had some relevance to, that I might find people who would know my mother or my father and by proxy, know me—in a way that might supersede all I knew of myself—was enticing. I wanted To Know. But when I tried to ask my father questions about the island, it was soon apparent that he had left too early to tell me much. When I asked my mother, who had lived there for twenty years before departure, her face would sour. Her answers? Always dismissive and curt. She spoke of it like a barren wasteland populated only by ghosts and overrun with tumbleweeds. The joys of her past were too encoiled in exhaustion and grief to extract enough to spare or share with me. Warsan Shire put it best: “Nobody leaves home unless home is the mouth of a shark.”

As a child, I understood.

The only person I knew who spoke of the country with any reverence was my grandmother. She was vocal about her dislike of the snowy New York winters. America meant nothing to her: it wasn’t shiny, it wasn’t “salvation” or a fresh start. It was just a place. Or even less than that, a layover. She was too old to dream of starting over with so much of her livelihood and identity tethered to another country. She had friends back home she kept in touch with regularly: I grew up scratching the foil off the back of phone cards with pennies, dialing phone numbers written on napkins in my grandmother’s shaky handwriting, listening to the operator tell me she had thirty minutes on the line (which was actually only fifteen; they always lied) and then counting the four or five rings before the call was answered cheerily by another old woman, at which point I quietly gave away the receiver. If I listened in, it was all gossip: status updates on a coming barrel, by the way guess who had just had a baby, and did you hear Miss Thing needed money after what she did to what’s-his-name, oh and so and so just died, what a shame. (Strangely, someone was always dead or dying.) The drama made the place more real. If I showed her a map of St. Vincent and asked her to point to where she was from or where my mother had been raised, my grandmother could tell me. With glee, even. There was no emptiness in her voice—only fondness and yearning. I latched onto that, desperate to soak up as much culture as I possibly could.

The years went on. I’m not sure how much culture I actually absorbed over the course of my adolescence, but the longing lingered without relent. As I grew older, I came to better understand my grandmother’s history, and this helped me make sense of my mother’s. My sisters and I eventually arrived at the conclusion that there was something strange about the woman raising us—something was wrong with her. We began to reflect on our childhoods and could now see her as she was: flawed and troubled and tragically human. When she managed to tell me anything about her past, what was obvious to me was that my mother had struggled and suffered in ways I could not quite grasp, and she had not healed from any of that, and then she had birthed six children back to back and raised them with such dysfunction that none of us had reached adulthood without deep emotional scars. Sometimes my siblings and I would look our parents dead in the eyes and ask, “Why did you do that? What were you thinking?”

They just looked through us and shrugged.

When I was a senior in high school, I wrote an essay about how everyone in our house was depressed, including the house itself. I won a $2500 scholarship. This felt validating, not only because it was the first official recognition of my writing, but because it meant that I had effectively described an emptiness so pitiful that a stranger was compelled to grant me money for it.

My parents did not attend the award ceremony.

My grandmother liked to read the subtitles on TV. I’d leave them on for her. She’d request the news channel in the mornings, and would mutter the words to herself slowly. I think she liked the practice. If my own mother had struggled to access books to read in the early 70s, there was no question that hers had read even less.

My grandmother liked to recite nursery rhymes to us and tell us stories. My mother would later reveal that she had no recollection of hearing a single one of these nurseries during her own childhood, which amused me to learn simply because it revealed the woman who had helped to raise me was distinct from the one who raised my mother.1

She’d talk about a woman she used to work for, who had raised a litter of nine “beautiful, well-educated daughters,” and the moral of this story was that my sisters and I should aspire to be equally successful by remaining focused in school. And there was a particular poem she’d recite often, to remind me and my siblings of the importance of keeping a household tidy:2

The cottage was a thatch’d one,

The outside old and mean,

Yet everything within that cot

Was wondrous neat and clean.

My grandmother also liked to talk about a book she’d read as a schoolgirl, titled, A Basket of Flowers Though she could barely recall the details of the story, she remembered with certainty how much she had loved reading it. Considering that she was born in 1928, I knew that her schooldays were decades past, so the significance of the impression this book had had on her was not lost on me. She begged me to buy her a new copy. I eventually obliged, ordering it from Barnes and Noble using my membership discount. And I read it myself, of course. It was surprisingly sad. My grandmother was thankful when I handed it to her, and read the pages to herself slowly in the night.

Written by French priest and teacher Christoph von Schmid, A Basket of Flowers was first published in 1755. Set in Germany, the book tells the story of a gardener, James, and his young daughter, Mary. They live a happy and humble life working in the Castle until one day Mary is accused of theft. The Countess’s prized jewel has gone missing and Mary is the only plausible culprit. She maintains her innocence, but she is convicted and exiled along with her sick and elderly father as punishment.

Throughout the book, for all her kindness and piety, misfortunate seems to often follow poor good-hearted Mary, but this is okay as long as she unwaveringly maintains her belief in God. And in the end, her pain is worth the peace that comes later—in fact, it is her pain that even makes it possible.

Suffering politely is the most virtuous thing one can do, says Christianity. And Mary does it so well.

My grandmother was kind and meek, like Mary. And, like her, so intimately familiar with suffering.

In the early 2000s, she got hit by a car one day while walking. With the money she won from her subsequent personal injury case, she was able to buy a little piece of land back home, and build herself a house.3 Out of pain came a possibility.

In 2017, she was finally able to return to St. Vincent, though it was only meant to be a short visit. It was the first time she actually got to live in the house she’d worked so hard to have constructed. But her peace was short-lived; a few months later she suffered a fall that reopened a fracture to her hip from a few years prior. Bedridden, she could no longer walk, and no one carried her to the hospital. In the weeks that followed, her wound grew increasingly and dangerously septic, and she died in that house.

The first time I finally managed to travel to St. Vincent as an adult, it was to attend my grandmother’s funeral. In a way, she was the one to bring me home after all. Out of pain, a possibility.

When my mother finds herself missing her mother, she rereads A Basket of Flowers. Although neither is or was an avid reader and both were limited to varying degrees in the level of education they received, I think there is poetry in the irony that a book is the thing that most connects my mother to her own.

I like to think that maybe, given the resources, my grandmother would’ve been a poet herself. Or a writer of some fashion. Like me. Maybe she would’ve written tragedies or fairytales, since that’s what she seemed to like. She clung so tightly to stories and literature, the little she had, telling them over and over until they became woven into the fabric of even our memories. I can’t recall if I ever showed her any of my writing. I wish I had bought her more books. Or read to her more. When I think of the poems and stories that she tucked into her heart, and the sadness at the core of them all, I wonder a lot about the totality of my grandmother’s life and all that she endured.

What if my love of the melancholy and the macabre is an inherited fascination?

I visit my grandmother’s house for the first time in January 2018, days after we—my five siblings and my parents and I—arrive for her funeral. Its exterior is rough and humble, like the cottage from the poem. But the inside of the house, thanks to the neglect of the uncles who for some reason now occupy it, is anything but neat and clean. Though its squalor is certainly wondrous.

It turns out that “Little Jim’s Cottage,” is not about the merits of good housekeeping but about a couple grieving their dying son:

The night was dark and stormy,

The wind was howling wild;

A patient mother knelt beside

The death bed of her child.

A little worn-out creature—

His once bright eyes grown dim,

It was a collier's only child—

They called him Little Jim.

With hands uplifted, see, she kneels

Beside the sufferer's bed;

And prays that He will spare her boy,

And take herself instead.

She gets her answer from the child,

Soft fell these words from him—

'Mother, the angels do so smile,

And beckon Little Jim.

'I have no pain, dear mother, now,

But oh! I am so dry;

Just moisten poor Jim's lips again,

And, mother, don't you cry.'

Below, the poem’s final stanza:

With hearts bowed down with sadness

They humbly ask of Him,

In heaven, once more to meet again,

Their own poor Little Jim.

(They say that children are not all raised by the same parents, and I think this is even truer for grandchildren than it is for siblings.)

(This was the only part of the poem she ever recited, and for a long time I thought that was the whole thing. But I later discovered there was a little more to it, that the poem was titled “Little Jim’s Cottage,” by Edward Farmer, an English poet. The cottage was a real place, it turns out. It once stood along St Helena Road in Polesworth, England. It was a cottage with a garden of flowers and butterflies, though it has since succumbed to damage from the elements.)

Growing up, she told me often about the house, how I could stay there anytime I visited as long as I wanted. That the house was for me.

This is what writing is all about. Thanks for sharing.

This was so so so beautiful. And powerful. And heartbreaking. Tragedy and inequity persists like a dog. But so too can healing. Thank you for sharing.